Seeing through Google's eyes: neural nets and computer vision

Many of the latest advances in image and audio processing (Facebook’s DeepFace, for example, or Google’s voice search) have come from developments in artificial neural networks, or “deep learning.” Neural networks are a type of statistical machine learning model inspired by the workings of the human brain. Like the human brain, their functionings are a little opaque, and we have little idea why they work so well. By exploring Google’s Deep Dream visualization approach, this post will introduce you to neural networks and some of the cool things they can do.

Deep dreaming at Swarthmore

Our vision and object detection systems recognize low-level features, such as corners and edges, as parts of larger features, objects, which we see in images.

Neural networks, in theory, work the same way. Neural networks are composed of a series of layers that each transform input a certain way (with lots of different kinds of layers). The lowest-level layer takes the raw input and maps it to a slightly different representation; each layer in turn builds on the output of the previous layer.

Ultimately, what each of these layers is doing is transforming the geometric space of the input data to try to distinguish between different types of features. At lower levels this means aggregating raw pixels into features like lines, corners, and edges; at higher levels this means aggregating corners and edges into squares and triangles and ultimately objects.

The mathematical processes by which this happens can be hard to comprehend, so a lot of energy has gone into trying to visualize these processes and make them more easily understood. As these networks become more complicated (check out the “Inception” architecture Google used to win ILSVRC 2014 below), it has become harder and harder to understand what the neural networks are actually doing.

A simplified map of Google’s Inception architecture

In June, Google published an example of a new visualization approach that has come to be called deep dreaming. To visualize the output of each of the layers individually, we create a feedback loop by feeding the output of that layer right back into it. By repeating this process several times, we’re essentially telling the layer to exaggerate whatever transformation it’s making to the image, helping us see what patterns the layer is recognizing.

A pre-trained version of the Inception architecture is easy enough to find online – if you’d like to follow along with the process or run your own deep dreams, I’ve added some annotations to K.P. Kaiser’s heavily-annotated version of the Deep Dream script here.

You’ll need to install Caffe to run it, which can be a pain – fortunately, I had some smart people to help me get it installed. Generating deep dream images takes seconds on the Swarthmore CS lab cluster.

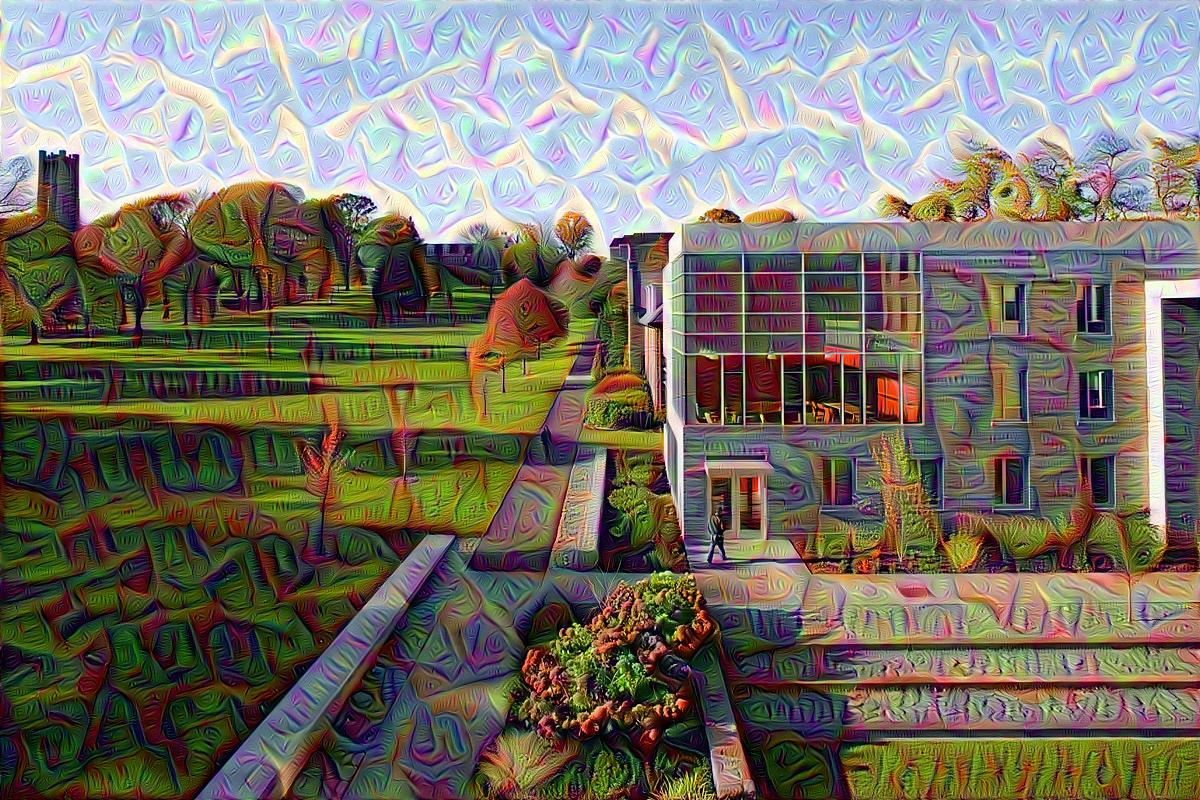

Here’s the input image we’ll feed into our neural network:

Input image, the view of Swarthmore from Alice Paul dormitory

Now we can look at what deep dream output looks like at various stages in the network. In order to exaggerate our features, the output below has gone through six octaves (that is, our feedback loop has passed through the layer six times).

Low-layer dream output

conv2_3x3_reduce

It’s hard to interpret this output literally, but what we can see is the structural patterns that the layer is exaggerating. This layer seems to act on lines and flows, creating a brush-like effect.

conv2_norm2

This layer appears to be starting to detect corners, arches, and other patterns formed by combining simple lines with corners. It doesn’t seem to be creating any macro patterns just yet, but these are the kinds of low-level features that are combined to recognize larger features.

Mid-layer dream output

inception_3b_3x3_reduce

Near the middle of the network we start to see combinations of low-level features into distinct patterns that start to resemble objects. Note that not only is the layer exaggerating borders, but it is also starting to generate features that it suspects might be there (the pair of eyes at the top left of David Kemp dormitory).

pool3_3x3_s2

As we start to pool together more features in higher-level layers, we can start to see why this visualization approach has been called Deep Dream. One of the effects of the feedback loop that we have constructed is that slight suspicions the model may have that something exists are exaggerated until we start to see these canine hallucinations.

If you’re curious why there are so many dogs in the picture, it’s important to remember that the neural network is revealing to us what it has learned: the training model used to generate these pictures, BVLC GoogLeNet, was trained on ILSVRC2012, which includes many pictures of animals. We’ll look at some output from a different data set after the next two pictures, which illustrate some of the different kinds of patterns grouped in higher-level layers.

Higher-layer dream output

inception_4d_pool_proj

In some of the higher layers (which have access to the feature transformations of all previous layers via their input), we start to see the more complicated patterns that gave GoogLeNet its edge: in this layer’s deep dream output we can see a combination of a variety of features across the range of the image.

inception_4d_3x3_reduce

The hope of researchers is that these kinds of specific micro-level hallucinations are evidence of comprehensive understanding in a higher layer of local information interpreted by lower layers. By enhancing recognized objects through the deep dream feedback loop, we have allowed the neural network’s curiousity to run wild; these visualizations help us see what it is capable of imagining.

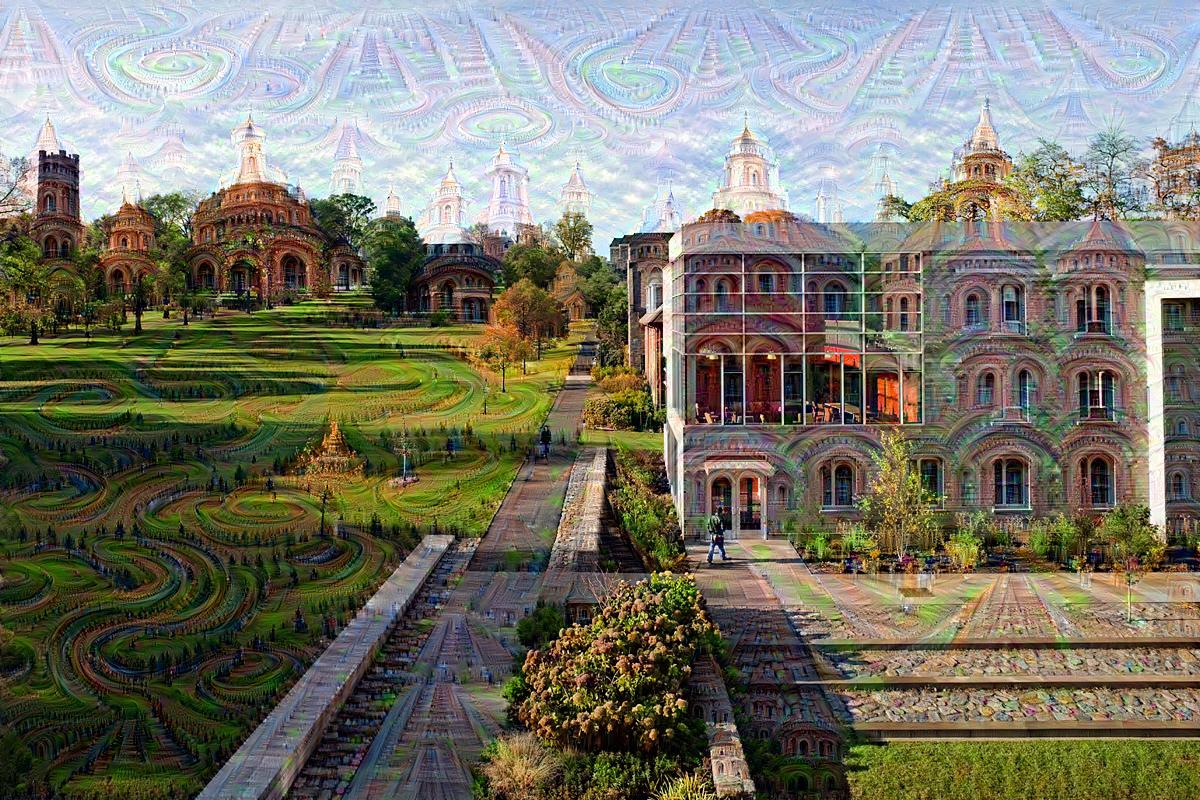

As mentioned above, the objects and features that the neural network can recognize are dependent on the training set used to train the neural network. The model learns to encode the input it has been given, as our learning environments shape our understanding. Deep dreem images from models trained on a places dataset, Places205-GoogLeNet, highlight different features:

Low-layer dream output

conv2_norm2

Again, we should be careful not to read too much into the visualizations that appear; rather, they serve to help us understand what kinds of patterns the neural network is learning to look for. This layer is dream output from a convolutional layer at the base of Google’s Inception architecture.

inception_3a_pool_proj

One way to abstract the output of deep dream is as revealing to us the filter being passed over the data, or the transformation being applied to the geometric space the data occupies.

Mid-layer dream output

inception_3b_pool

Again, mid-level layers seem to aggregate features selected by low-level layers.

pool3_3x3_s2

As these patterns combine at higher levels, we start to see some gorgeous visualizations.

High-layer dream output

inception_4a_output.jpg

The different types of hallucinations output by the Places deep dream serves as an important reminder that our models will always be limited to our training data. If we train our model to recognize buildings and geographic features, it will be unable to recognize animals, and vice versa. The hallucinations reflect this.

inception_5b_5x5_reduce

Some critics of neural networks say that their relative performance advantages stem from micro-optimizations made possible by huge computational power (Google and other researchers). A perhaps more significant advantage available to Google is their access to data – with more data to train on, neural networks can be trained to represent larger ranges of input.

That being said, neural networks are incredible tools for learning representations of data and combining data in new and interesting ways (transfer learning is suuuuper interesting). A paper was recently published about applying the style of one image to another, leading to some awesome visualizations.

The style of Munch’s “The Scream” being applied to a picture of the Eiffel Tower

If you want to get a closer look at each layer of the deep dream output, check out output from one run on the image recognition dataset and the places dataset, or dream your own picture. Or, you can run this yourself!