Reflections on SemEval2015

As a part of the Natural Language Processing class I took with Rich Wicentowski last fall, teams of students competed to build machine-learning models that could accurately predict the sentiment of Twitter data for SemEval 2015, the International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation. Given that I spent a summer building commercial machine classifiers, I’ve had some time to reflect on the first machine learning model I built.

Given that we had been exposed to natural language processing for only a couple months, our results were fairly impressive: our best model was predicted sentiment with an F-score of 57.2, which is pretty close to the industry standard. The winners of SemEval 2015, out of over 40 teams, was Bauhaus University, Weimar with an F-score of 64.84.

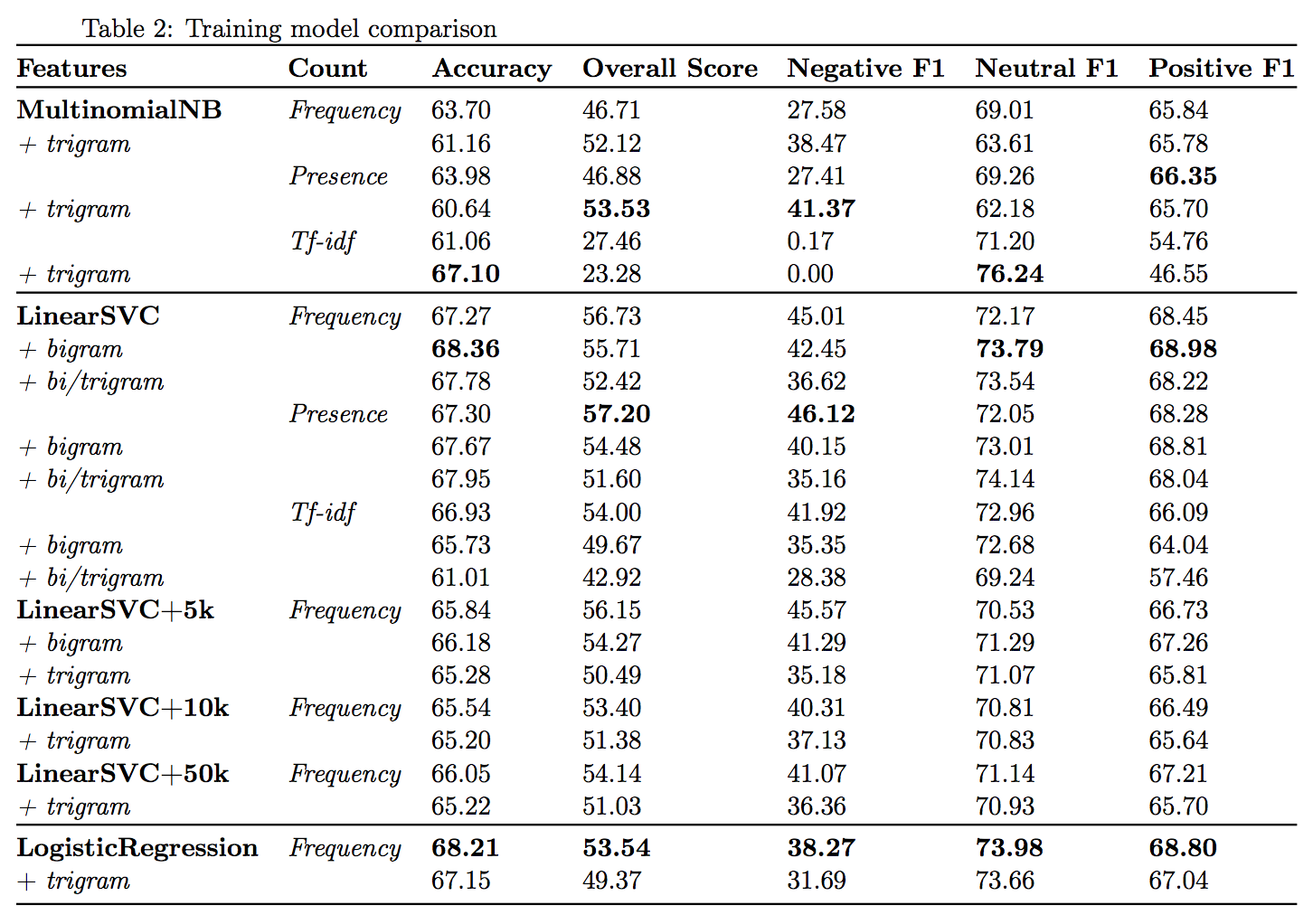

We weren’t competing for the top, though. I worked with a friend, Alec Pillsbury, and we wanted to tease apart the differences between the different pre-processing techniques and models that we had learned about. We found our way to scikit-learn, which allowed us to easily swap out models and tweak parameters for our bag-of-words feature (cheatsheet that I wish we’d had around). This made it easy for us to run a whole bunch of tests and spit out a big wall of numbers:

These numbers are cross-val results for different configurations of a bag-of-words model trained on 8111 tagged tweets.

We were a little pressed for time putting together our write-up (finals), so I didn’t spend too much time worrying about the presentation of data. Each row represents a different configuration (bigram, bigram + trigram, etc.) of our machine-learning models, and each column represents a different performance metric. The bolded numbers represent the local maximums, the configurations of our bag-of-words model that gave the best metrics.

Our most significant finding, in retrospect, was that negative models tended to perform better when bag-of-words weighted by presence rather than frequency, which isn’t very surprising for a couple reasons.

Other than that, it seemed that little we did improved the models or affected it at all. We tried some lazy bootstrapping, adding 50 thousand tweets from the Sentiment140 corpus, but found that it actually hurt our results, probably because it’s a dirty dataset. We clearly see elsewhere danger of noise in a sparse dataset: almost every single bigram configuration performed better than its trigram configuration.

While I was building models this summer, we spent a fair amount of time discussing feature selection and dataset composition: the most significant ways we could improve the models, we found, were by changing the features selected and cleaning up the data – as well as increasing the size of the training set. That being said, ultimately, our attempts to try different feature sets didn’t lead to any significant breakthroughs, other than that less was more with sparse data. Given that language data tends to be sparse, trigrams tended to hurt our models more than help them. Oh well.